Interview by Rebecca Rashkoff

Mack Baker (they/them) is a transdisciplinary artist in the Ceramics Master of Fine Arts program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In the Summer of 2022, Mack was awarded a visiting fellowship at the International Summer Academy of Fine Arts in Salzburg, Austria. They previously spent four years living and studying in Burlington, Vermont before moving to Boston, Massachusetts for a one-year program at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Their mixed media approach highlights the queer experience, in all its vibrancy and communal care. Moving between clay, drawing, and photography, Baker wants their work to be a guide for how we love and care for each other. This April 1-22, Baker will be participating in SPACORE, a group performance and installation show which satirizes wellness culture, at the Co-Prosperity (3219-21 S Morgan St) gallery in Chicago. They also have a solo exhibition at Lillstreet Gallery this Summer.

Note: This interview was conducted in August 2022. Since then Baker has shown their work in an additional four shows, and has five exhibitions on deck in Spring 2023.

Hey Mack! Thanks for taking the time to sit down and chat today. To start off, I’d love to hear about your work, specifically your ceramics, which uses vibrant colors and varies between sculpture and utility. Can you tell us a bit more about your conceptual framework?

The queer experience is really important to what I’m doing right now. I focus on community and bringing people together. I’ve been trying to reimagine Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party piece. She created a set of ceramic plates with depictions of a wide variety of vulvas. The work is lauded for being a juxtaposition between craft and conceptual art. Her work is considered a seminal feminist contemporary artwork of the late 70s. What I really feel is missing from this work is the people and the food, two important parts of any dinner party. The utilitarian potential of the work feels like a missed opportunity to me. Making and sharing food around the dinner table is the way that I build community, and I do my best to bring it into my artistic practice. I don’t want it to be commodified or turned into a gimmick, which is why I try to implement it into my practice in a thoughtful and considerate way.

When I think about how to show up for the queer community, I think about ways that we can nurture each other with our time and energy. In my life and work, I nurture through food and feeding my comrades. Before I left this past summer for Salzburg, I had my first plate dinner. I planned the dinner for months, methodically throwing plates for each guest, fired them with vibrant glazes, and wrote a queer-themed protest phrase on the face of the plate with golden luster, carved into its surface, or piped with colored liquid clay. I invited guests to bring an object that was meaningful to them and I served them a meal that I had cooked with my partner that day, sourcing the ingredients locally. After the meal, I had every guest hold the plate they had eaten from and I took their portrait in my living room. I think about rebuilding homes and reclaiming the dinner table itself for the queers. The nuclear family’s dinner table can be a place of trauma, or at the very least, discomfort and stress, for a queer person, so my hope was to reframe that narrative for those I love and care for deeply. If I am able to find a way to make my community feel welcomed because of who they are, not despite it, my work will feel meaningful.

Can you tell us about how studying in Vermont influenced your choice to pursue your Master of Fine Arts in Ceramics? How has the structure and community of the MFA program impacted your work?

As a part of my final semester at the University of Vermont (UVM), I pulled off a successful solo exhibition. I threw ten phallic closed forms reaching heights of 5 feet in porcelain, drew 5-by-4-foot illustrations using a yonic pattern, and projected these drawings upon the forms in a moving loop. The result was a gallery filled with yonic projections moving across the phalluses and the viewers, including my professors and family. In my junior year, in addition to my B.S. in Psychological Science, I shifted my focus to my work as an artist and sought a major in Studio Art. The Arts Department extended my show because of its success, and it was a wake-up call for me. I realized that I loved working between mediums. In the show, I used drawings, projections, and ceramic sculptures. I also designed housing for the projectors so that people could walk around the work and interact with the projections without causing shadows interjecting with the work. I had to learn so many skills for this exhibition, and I leaned heavily on the department’s studios, workshops, and mentors. I got certified in the woodshop and I had to write a grant to fund the purchase of media players. I was doing all the things that I needed to develop a professional practice but at a smaller scale. Applying for funding and building the projector housing are skills that I didn’t previously consider as part of my practice or necessary to it, but learning these skills are what it takes to be a working artist. As soon as the show was over, I was ready to do it all over again.

At UVM, I was involved with a couple of different art collectives, but they just felt so insular and not quite big enough, so my partner and I knew that we needed to move. I applied to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where I did a post-baccalaureate program. Because I was studying during the pandemic, everything was online, but I really just needed access to the studio. I created a series of drawings that I was really excited about, and I got into the habit of getting to the studio every day, receiving feedback, and knowing where to look for the right feedback. I also developed a concrete writing practice so that I could successfully apply to programs and residencies.

Most importantly, I learned how to talk about my work. Having that kind of focus got me into every Masters of Fine Arts program I applied to. I am currently a student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Now that I’m based in Chicago, I’ve been able to get opportunities that are outside of the university, both within the city’s limits and internationally. I think what SAIC does well is they really give you opportunities. They help you build a name for yourself. Going into my second year, I have six shows on deck, including university-hosted shows and exhibits across the city.

How do you see the distinction between art and craft playing a role in your ceramic work?

I grew up in a small New England town with my mother, who has always been a lover of handmade domestic objects. All of the plates we ate off of were thrown by potters in Vermont and Western Massachusetts. Craft is really emphasized in New England as being separate from fine art, and that has been sort of a thorn in my side growing up. I even felt that way when I moved to Vermont. Gallery opportunities in Burlington are very focused on craft and highly saleable items to people like my mom. I don’t want to discredit craft and artisanship because I think that those are two important pillars of the way that I approach ceramics. The way that I consider form is craft-based. I’ve been told by many people that I should make molds of my plates so that I don’t have to throw every single one of them. I decided not to do that because the labor involved with each plate is an act of care, and that is part of my practice as well as my conceptual framework. I was a production potter at the end of high school, which means I created hundreds of hand-thrown pots for sale. If I had gone down the apprentice route, my life would look a lot different, but I think that the skill and the thought involved with artesian ware is something I bring to my conceptual practice, and that is pretty specific to my approach.

I know that this past Summer you received the Seebacher award from the Austrian American Foundation to attend the Summer Academy of Fine Arts in Salzburg, congratulations! Can you tell us about the exhibit you created while participating in this residency and about your overall experience at the residency?

I worked with Anna Daučíková, who is an incredible Slovak photographer. In the 80s, she created this photo series about gender that was way before her time. She made self-portraits where she pressed plates of glass against her chest and took her self-portraits on black and white film. She has this beautiful, subversive perspective on queer strategies within visual art and performance. While I was at the Academy in Salzburg, I took part in a group performance called “Chants on Camp,” which was inspired by Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp.” Sontag’s essay is an interesting essay because it’s laid out in bullet points. Some of her points even contradict others because camp is inherently contradictory. It’s both self-aware and not, because as soon as you begin to talk about it, you remove the mystery involved with how people perform their identities. Every member of the performance claimed a passage that resonated with us. We then chose four words to have the group chant as we stepped up onto the stage. We each chose to do an interpretive performance, read a section of the passage, or read our interpretation of the passage. Although a lot of my work is performative in nature, I don’t always consider it performance. Still, I wanted to be a part of something like this while I was there because of the rich history of performance art in Austria, specifically in Vienna, in regard to Valie Export and Viennese Actionism.

The performance was part of a larger exhibition open to the public, which I wasn’t aware of when I arrived. The Academy itself is in the Festung (Fortress) in Salzburg and it’s literally a tourist attraction, so tourists would just walk into the Academy, since they paid entrance to the fortress. It made for a bizarre place to make work because it has such an imperialist, patriarchal presence. We can talk more about what I actually did because it’s a pretty funny story. I wanted to do something that was site-specific, since this fortress was so unique.

This past summer, I worked for Rirkrit Tiravanija, a Thai conceptual artist, and Wrightwood 659 (659 W Wrightwood Ave), a museum gallery in Lincoln Park, Chicago. The piece that I was hired to work on was called “Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Green?” It involved a group of artists live-drawing images, in charcoal, of social uprisings from Bangkok, Washington D.C., and Chicago, because those are the three cities where the work has been exhibited. All of the drawing happened while gallery guests watched. We were working from images that are within the public domain, so oftentimes, people would recognize the famous newspaper photos we were drawing. Curry was also served in the gallery. The three flavors of curry they served were red, yellow and green, which are colors important to Thailand’s culture and are connected to historical protest movements in the country. Many of the original protest images and the first exhibition were related to the military coup that was happening in Thailand in the early 2000s.

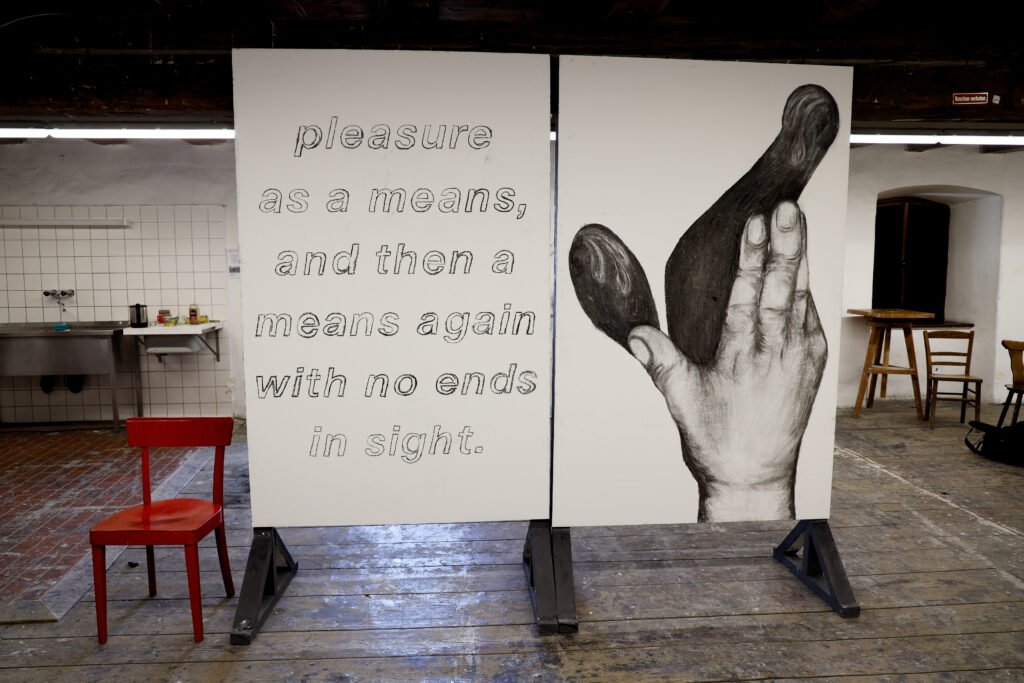

While I was working on this show, I was working 8-12 hours a week for three months, drawing on the walls with charcoal, working really large. And when I left for Austria, I was like, ‘Wow, I actually kind of miss this.’ I loved drawing on the walls. The studio spaces and classrooms at the Summer Academy are actually intended to be filled. They have these white panels on the walls so that if you want to hang up work, you don’t hang it on to the actual wall because it’s a castle from the 1400s. These panels are pristine white because they repaint them all the time and they were just calling to me. Luckily, I had a ton of charcoal with me. I started making these sketches of double-ended dildos because I’ve been really interested in them as an art object. I think that they represent confrontation with heteronormativity and traditional norms associated with sex and intimacy.

I also titled the work using different sections of this poem by Eileen Myles called “Peanut Butter.” The poem talks about pleasure and love and sex as not having a means to an end, but more of a continuous rediscovery and ongoing practice of joy and care. Seeing this work in person, you’re confronted with the material. The sensuality of the charcoal is disarming in a way. It’s almost like you have to register what you’re seeing after you’re already in it, observing and enjoying it for what it is. I really love that quality of charcoal. I think it might actually be something that I continue to do. I’m writing proposals for site-specific installations with charcoal to continue this practice. I really enjoyed the act of just drawing to draw, and not having any product at the end that could be then bought or transported; it was truly pleasure for pleasure’s sake.

Do you feel like the residency encouraged you to explore new topics and use a mixed-media approach? How did your experience at this residency compare to your MFA?

I think it was just sort of natural. In class leading up to the week of the exhibition, we were talking a lot about pleasure and queer relationship dynamics. So, when I pitched my idea everyone was just like yes just do it, we need dildos. When I had time off, I would just sort of walk around Salzburg and come up with these sketches, which were from memory. It felt like I had a lot more, I don’t know, liberty to just draw what I wanted to draw. And I ended up working quickly, so I did two 4 x 6 panels and then two, like a diptych, so narrow side by side and I think the dimensions for that were 3 x 6.

I think my MFA is very much like a free for all. It’s not that anybody would not encourage it, I just don’t have the space to really think as I did in Salzburg because it’s such a fast-paced environment. At the residency, it just felt like a perfect storm of having people around me who supported the vision. The director of the Academy said during the exhibition, “you know, when we think of gay art we see a lot of penises, and frankly, not enough dildos” so I thought that was a nice accolade *laughs*.

Do you feel like the residency encouraged you to explore new topics and use a mixed-media approach? How did your experience at this residency compare to your MFA?

I think it was just sort of natural. In classes leading up to the week of the exhibition, we were talking a lot about pleasure and queer relationship dynamics. So, when I pitched my idea, everyone was saying, ‘Yes; just do it; we need dildos.’ When I had some time off, I would just walk around Salzburg and come up with these sketches, which were from memory. It felt like I had a lot more liberty to just draw what I wanted to draw. I ended up working quickly, so I did two 1.2m x 1.8m panels and then two more as a diptych. Each of the dimensions for those drawings were 0.9m x 1.8m.

Comparing my MFA to this residency is hard. I think it’s just more of a fast-paced environment in art school in general, so it was nice to have a break to focus on just one project. At the academy, it just felt like a perfect storm of having people around me who supported the vision. The director of the Academy said during the exhibition, “you know, when we think of gay art we see a lot of penises, and frankly, not enough dildos,” so I thought that was a nice accolade *laughs.*

Is there an opportunity for you to return to the Academy in Salzburg and would you consider coming back to Europe?

I hope to. I’d really like to go back for longer. I made friends with a few folks who work at the academy, so it would be nice to visit again. I used to live in Copenhagen and I’m curious about Berlin, so there are a few opportunities I’ve been looking into, but I have to finish my MFA first.

It sounds like you have a lot on deck in terms of shows and working toward your thesis. Do you have specific goals you’re after or are you open to whatever opportunity comes around? Specifically, do you have an idea of where you’d want to be geographically, or what sort of work you’d be interested in?

I think one of the beautiful things about being an artist is that you can move around, you can travel. I do love teaching, but I want to pursue residencies and fellowships before I find somewhere to teach. I’m applying to a Danish ceramic residency for the fall, so I hope they’ll have me. I’m also looking into showing in the European market, so I’ve just been looking for open calls and meeting with curators. It would be nice to come back, I had such a good time.